All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Utilization of Eggshell Powder in Cement Mortars: Enhancing Mechanical and Thermal Properties for Sustainable Construction

Abstract

Introduction

Given the critical role of cement in the construction industry and its significant impact on global climate change, there is an urgent need to develop alternatives to the traditional clinker-based cement. In this study, the Eggshell Powder (ESP), used as a partial cement replacement in mortar, with an emphasis on its thermal behavior, passive indoor temperature regulation, and synergistic interactions with multiple supplementary cementitious materials, namely, Fly Ash (FA), Silica Fume (SF), and Blast Furnace Slag (BFS), was investigated. The effects of ESP on shear strength were also investigated, as they have not been extensively documented. Distinctively, this research implemented a large-scale screening of 60 mix designs (360 specimens) to maximize cement reduction while maintaining, or even improving, mechanical performance relative to the control.

Methods

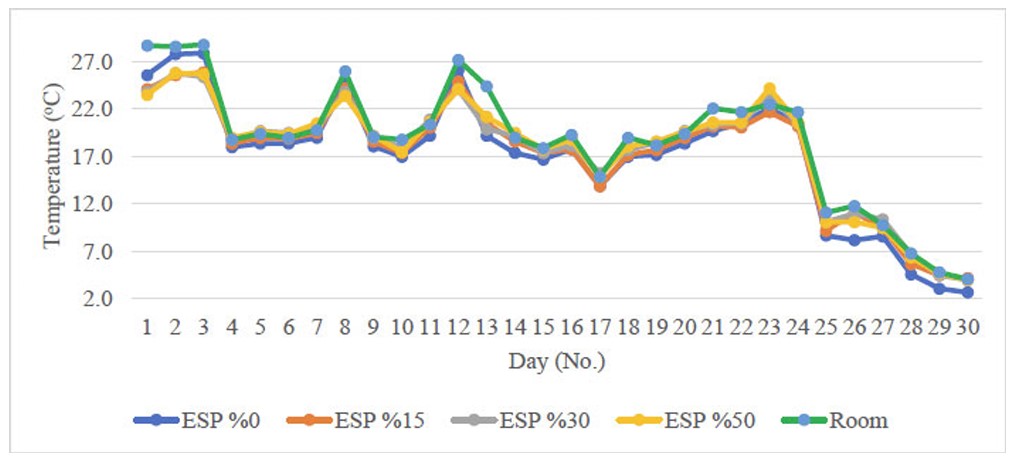

Mortars with ESP at 0, 10, 15, and 20 wt.% were tested for flow (EN 1015-3) and flexural and compressive strengths at 7 and 28 days (EN 196-1). Shear strength at 28 days was measured using the Z-push-off method. Blended (ternary and quaternary) mixes replaced 30 wt.% of cement through combinations of ESP, FA, SF, and BFS. Thermal behavior was monitored using chambers (7 × 15 × 15 cm; wall thickness = 4 cm) made with 0, 15, 30, and 50 wt.% ESP over 30 days, with temperature readings taken at 09:00, 12:00, 15:00, 19:00, and 00:00 via type-K thermocouples. Results were summarized as average values.

Results

Workability decreased beyond 15 wt.% ESP. The best blended mix (70% cement, 10% ESP, 10% FA, 5% SF, and 5% BFS) exhibited a 12% increase in 28-day compressive strength and a 17.1% increase in 28-day flexural strength compared to the control, while the mix containing 10 wt.% ESP reached a 28% shear strength in 28 days. ESP-modified mixes exhibited an improved passive thermal response, with peak internal temperature reductions of up to ≈ 7°C during hot periods (≈ 12:00– 15:00) and comparable or slightly higher internal temperatures during cooler periods.

Discussion

ESP dosages of 5-10 wt% can enhance mechanical performance if they are combined with FA, SF, and BFS. This is likely due to filler densification and nucleation effects in addition to limited pozzolanic activity. Thermal monitoring showed that ESP improves passive regulation under variable ambient conditions. However, the practicality of higher ESP levels (> 15 wt.%) decreases due to increased water demand and reduced workability.

Conclusion

Within SCM-blended systems, ESP provides a cost-effective and eco-efficient approach to reducing cement while maintaining or even enhancing mechanical strength and thermal comfort. However, the findings are limited to laboratory-scale and short-term curing conditions (7–28 days). Therefore, future research should extend to long-term durability assessments, such as freeze–thaw resistance, chloride ion penetration, and sulfate attack, along with microstructural validations (SEM, XRD, TGA), building-scale thermal analyses, and techno-economic evaluations to establish the practical feasibility of ESP-modified mortars for sustainable construction applications.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sustainable construction aims to reduce the environmental footprint of buildings throughout their lifespans. This includes reducing their energy consumption, emissions, and the amount of resources used. The partial replacement of cement with materials that have been recycled or are renewable is one key strategy for lowering the CO2 emissions that are associated with the construction industry.

In the last ten years, rice husk ash, palm oil fuel ash, wood ash, oyster shell powder, and other agricultural and industrial by-products have been investigated as materials that could substitute for cement due to their pozzolanic reactivity and contribution to waste valorization [1-5]. However, one possible substitute is eggshell powder. Eggshell powder is particularly promising because it has a high calcium carbonate content and is widely available as food-industry waste. This makes it both environmentally and economically attractive for sustainable cementitious composites [6].

Concrete is fundamental to the world's economy and social development, and because its demand is high, it has a significant environmental impact through cement production. From 2005 to 2020, global cement output increased from 2.3 to 3.5 billion tons (≈ 2.5%/year), and projections for 2050 indicated 3.7–4.4 billion tons [7]. Cement production contributes to climate change because manufacturing it is energy-intensive, depletes natural resources, and emits substantial CO2 [8, 9]. The construction sector is currently responsible for about 36% of global energy use and 39% of total CO2 emissions.

Therefore, partial cement replacement strategies are urgently required to reduce the environmental footprint of these composites [10].

A possible solution is eggshells, which are a common agricultural waste, constituting approximately 10% of an egg’s weight, and are primarily made up of CaCO3, a key component relevant to cement systems [11, 12]. More than 8 million tons of eggshells are thrown away every year. If not properly managed, this waste can cause environmental pollution, odor issues, and allergic reactions [11, 12]. Using Eggshell Powder (ESP) to replace cement partially would not only alleviate the environmental burden of eggshell waste but also advance sustainability in construction materials.

According to prior studies, Eggshell Powder (ESP) is a viable and sustainable substitute in cementitious systems. Although eggshells are linked to environmental concerns as waste, they can also potentially absorb heavy metals and mitigate pollution [13]. ESP has a high CaCO3 content and low concentrations of deleterious ions (e.g., chloride) that could impair durability [14], which makes it a promising alternative to limestone powder in cement production [15].

Incorporating ESP into cement could have many benefits, including conserving natural resources, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and lessening the environmental burden of bio-solid waste [16-21]. ESP also lacks harmful chemical constituents that would adversely affect concrete properties [20, 22–, 23]. Numerous studies have reported mechanical improvements, compressive, tensile, and flexural, at optimal dosages typically around 5–15 wt.% [1, 22, 24-30], while higher replacement levels may reduce strength [1, 19, 31, 32]. ESP can also refine the pore structure through its micro-filler effects and hydration-related reactions during curing. It thereby contributes to enhanced durability [33-35] (although the precise optimum can depend on particle-size distribution, curing regime, and co-use with SCMs [36]).

Flexural strength has also been extensively studied in concretes incorporating ESP [8, 16, 18, 37, 38]. For example, a mixture containing 5% ESP and 10% microsilica achieved flexural strength values comparable to the control [39-41]. Conversely, some studies reported up to 22.9% gains when ESP acted primarily as a filler at contents up to 20% [63], and approximately 7.5% ESP has been identified as an optimum level for peak flexural strength in certain mixtures [42-45]. These findings indicate that flexural response is dosage- and system-dependent, influenced by particle-size distribution, curing regime, and co-use with SCMs.

Despite notable progress, clear gaps remain in the literature. Most studies focus on short-term mechanical responses, while long-term behavior under sulfate, chloride, and acid attack, as well as freeze–thaw and wet–dry cycling, has not been sufficiently investigated [19]. Evidence on the thermal characteristics of ESP, including its potential contribution to passive indoor temperature regulation, remains limited, as do data on building-scale energy impacts and scale-up.

This study directly targets these gaps by evaluating the compressive, flexural, and shear strengths of ESP-based mortars across multiple replacement levels, by examining thermal response under repeated daily cycles relevant to indoor comfort and operational energy, and by systematically mapping multi- SCM interactions [46] in ternary and quaternary blends of ESP with Fly Ash (FA), Silica Fume (SF), and Blast Furnace Slag (BFS) [5, 47]. To that end, the study conducted a large-scale screening of 60 mixes (360 specimens) explicitly aimed at maximizing cement reduction without compromising strength, discussed environmental and practical considerations, and identified detailed techno- economic validation as a direction for future work. By integrating mechanical, thermal, and shear performance with multi-SCM effects, this approach provides decision-ready evidence for sustainable mortar formulation and helps frame priorities for durability and scale-up studies.

2. MATERIALS USED IN RESEARCH

The primary materials used for producing cement-mortar specimens in this study were Portland cement, sand, water, Eggshell Powder (ESP), Fly Ash (FA), Silica Fume (SF), and Blast Furnace Slag (BFS). The characteristics and preparation procedures of these materials are summarized below.

A general-purpose Portland cement (CEM I 42.5 R) was used in this study. The cement conformed to TS EN 197-1 standards, with a specific gravity of 3.15 g/cm3 and a specific surface area of 3350 cm2/g. The physical and mechanical properties of the Portland cement are presented in Table 1, and these data were obtained from the manufacturer’s technical datasheet. Likewise, the chemical compositions listed in Table 2 for cement, fly ash, blast furnace slag, and silica fume were primarily derived from manufacturer-provided documentation.

| Density (g/cm3) | 3.15 | Specific surface – Blaine (cm2/g) | 3350 |

| Setting time start (min) | 150 | Compressive strength (2 days) (MPa) | 28.6 |

| Setting time finish (min) | 190 | Compressive strength (28 days) (MPa) | 55.8 |

| Volume expansion (Le Chatelier) (mm) | 1 | - | - |

Class F Fly Ash (FA), sourced from local suppliers, and Blast Furnace Slag (BFS) obtained from the Ereğli Iron and Steel Factory in Zonguldak, Türkiye, were used in the mixtures. Silica Fume (SF) was procured from the Antalya–Etibank Ferro-Chromium Factory. The silica fume had a specific gravity of 2.32 g/cm3 and a unit weight of 245 kg/m3. The chemical compositions of the cement, fly ash, blast furnace slag, silica fume, and eggshell powder (ESP) are presented in Table 2.

Natural sand was used in the mixtures. The sand was thoroughly washed to remove impurities and sieved to obtain a suitable particle-size distribution for cement-mortar applications. The particle-size distribution of the sand is presented in Table 3, confirming that the material is well-graded and suitable for use in the mixtures. Tap water maintained at 23 ± 2°C was used for mixing and curing the specimens.

The Eggshell Powder (ESP) used in this study was supplied by a certified agricultural manufacturer (Agrobera®, Türkiye), which produces feed additives and agricultural-grade calcium supplements from eggshell waste. The supplier ensures full traceability under national feed additive regulations through registration code YK-TR-4200434. The raw eggshells were collected from local bakeries and food industries under controlled conditions to prevent contamination.

Before processing, the eggshells were thoroughly washed to remove impurities and organic residue, then air-dried in sunlight for 24 hours. The shells were then dried in an oven at 120°C for 24 hours to remove any remaining moisture.

The study selected 120°C as the drying temperature in order to eliminate residual moisture and organic matter without causing the thermal decomposition of CaCO3. This is similar to other non- calcined ESP preparation methods (drying at 105–120°C for 24 h) that were reported in previous studies [31, 40]. This approach preserves the natural CaCO3 structure of the eggshells, allowing them to function primarily as a bio-filler rather than a pozzolanic additive.

After thorough drying, researchers ground the eggshells using a mechanical grinder and then sieved the powder to obtain a particle size range of 60–90 µm, comparable to cement fineness. Any visibly contaminated or blackened shells were removed before grinding to ensure uniformity. Using manufacturer analysis, the physical and chemical characteristics of Agrobera® ESP were verified. The results indicated a calcium content of approximately 35.4%, magnesium content of 2619.7 mg/kg, moisture content of 1.42%, and no detectable pathogenic microorganisms (E. coli < 10 kob/g; Salmonella spp., negative). The powder’s color ranged from white to light beige, consistent with the supplier’s specifications for agricultural-grade calcium material. Both the consistency and the traceability of the ESP used in the experiments were ensured using these procedures.

In this study, a polycarboxylate ether-based superplasticizer (Melflux 2651 F, BASF) was used in all mortar mixtures to improve workability without requiring additional water. The admixture was used at a fixed dosage of 0.5% by weight of the total binder (cement + ESP). Melflux 2651 F was chosen for its high dispersing efficiency and compatibility with calcium carbonate-rich systems, such as ESP. The superplasticizer was dissolved in the mixing water before blending with dry materials to ensure homogeneous distribution.

3. EXPERIMENTAL WORK

The mortar mixtures were prepared in accordance with EN 196-1. A constant water-to-binder ratio (w/b) of 0.50 and a sand-to-binder ratio of 3:1 were maintained for all mixtures. Eggshell powder (ESP) was used as a partial replacement for cement by weight at 0%, 10%, 15%, and 20%. The exact proportions of cement, ESP, sand, water, and superplasticizer are presented in Table 4.

All dry materials were first mixed for 2 minutes, followed by the gradual addition of mixing water containing the dissolved superplasticizer. Mixing was continued for an additional 3 minutes to achieve uniform consistency. Workability was evaluated using the flow table test (EN 196-1), and the target flow value was maintained at 110 ± 5% for all mixtures to ensure comparable fresh-state properties between the control and ESP-modified mortars.

| Chemical Component | Cement CEM I 42.5 R | Fly Ash (F Class) | Blast Furnace Slag (BFS) | Silica Fume (SF) | Eggshell Powder (ESP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 20.63 | 58.58 | 41.49 | 85.98 | 0.59 |

| Al2O3 | 4.71 | 23.40 | 16.34 | 0.64 | 0.15 |

| Fe2O3 | 3.41 | 6.97 | 0.61 | 0.32 | 0.04 |

| CaO | 63.64 | 1.55 | 29.26 | 0.7 | 51.40 |

| MgO | 1.24 | 2.76 | 7.68 | 4.9 | 0.54 |

| SO3 | 2.98 | 0.45 | 1.90 | 0.63 | 0.81 |

| Cl- | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | - | 0.09 |

| Na2O | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.80 | - | 0.44 |

| K2O | 0.91 | 4.11 | 1.10 | - | 0.09 |

| Particle Size, mm | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % fine | 100.0 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 62 |

| Sample # | Eggshell Powder % | Silica Fume % | Fly Ash % | Blast Furnace Slag % | Flow Table Test (Cm) | 7-Day Flexural Strength (MPa) | 7-Day Compressive Strength (MPa) | 28-Day Flexural Strength (MPa) | 28-Day Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14,1 | 4,68 | 15,24 | 5,02 | 18,21 |

| 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14,7 | 4,38 | 14,68 | 6,21 | 18,92 |

| 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14,5 | 4,29 | 15,47 | 6,78 | 20,64 |

| 4 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13,8 | 3,57 | 11,87 | 4,68 | 15,67 |

| 5 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13,5 | 2,98 | 9,69 | 4,09 | 12,43 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14,4 | 4,96 | 17,99 | 5,67 | 19,99 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 14,6 | 5,15 | 17,45 | 5,78 | 22,04 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 14,9 | 4,47 | 13,79 | 5,28 | 17,12 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 15,1 | 3,83 | 10,69 | 4,32 | 13,42 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 15,8 | 3,47 | 10,73 | 3,74 | 12,75 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14,3 | 5,12 | 17,79 | 6,20 | 20,60 |

| 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 14,6 | 4,11 | 17,43 | 5,92 | 21,16 |

| 13 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 15,1 | 4,49 | 20,36 | 5,57 | 22,12 |

| 14 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 14,7 | 4,15 | 15,66 | 5,45 | 19,87 |

| 15 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 13,9 | 4,92 | 15,63 | 6,04 | 19,98 |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14,1 | 4,72 | 18,01 | 6,68 | 19,34 |

| 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14,5 | 5,53 | 20,82 | 7,50 | 22,19 |

| 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14,9 | 5,42 | 20,77 | 7,73 | 22,37 |

| 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 15,6 | 4,73 | 17,56 | 6,02 | 20,38 |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 16,4 | 4,12 | 11,52 | 5,95 | 17,69 |

| 21 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 14,1 | 5,03 | 17,91 | 6,82 | 21,22 |

| 22 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 14,8 | 4,07 | 13,40 | 6,10 | 17,43 |

| 23 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 14,3 | 4,89 | 14,62 | 6,65 | 20,95 |

| 24 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 14,8 | 4,78 | 15,71 | 6,93 | 20,76 |

| 25 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 14,6 | 3,56 | 11,00 | 5,21 | 14,52 |

| 26 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 14,8 | 2,52 | 7,77 | 4,01 | 11,07 |

| 27 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 14,30 | 2,80 | 6,96 | 3,48 | 9,13 |

| 28 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 14,60 | 2,69 | 8,04 | 3,84 | 12,61 |

| 29 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14,6 | 4,22 | 15,70 | 5,62 | 21,90 |

| 30 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14,9 | 4,67 | 15,98 | 5,78 | 20,28 |

| 31 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14,2 | 3,38 | 8,91 | 3,72 | 12,59 |

| 32 | 20 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 13,8 | 3,15 | 7,28 | 3,85 | 9,38 |

| 33 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 14,3 | 3,00 | 15,01 | 3,35 | 17,68 |

| 34 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 14,2 | 2,98 | 14,58 | 4,07 | 15,35 |

| 35 | 15 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 13,7 | 2,54 | 8,82 | 3,81 | 12,75 |

| 36 | 20 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 13,2 | 2,64 | 8,05 | 3,23 | 9,92 |

| 37 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14,8 | 4,14 | 14,60 | 4,28 | 16,31 |

| 38 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14,7 | 4,56 | 15,87 | 6,14 | 20,21 |

| 39 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14,1 | 3,72 | 13,39 | 4,41 | 15,18 |

| 40 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 13,6 | 3,75 | 11,43 | 5,48 | 14,97 |

| 41 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14,3 | 3,37 | 9,86 | 4,05 | 12,89 |

| 42 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14,6 | 2,89 | 7,45 | 3,04 | 9,25 |

| 43 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 13,9 | 2,74 | 6,52 | 2,95 | 8,48 |

| 44 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 13,7 | 2,20 | 4,46 | 2,34 | 5,82 |

| 45 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 14,5 | 4,61 | 13,21 | 5,47 | 16,56 |

| 46 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 14,3 | 3,47 | 10,64 | 4,09 | 13,21 |

| 47 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 14,1 | 3,64 | 12,19 | 4,35 | 17,69 |

| 48 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 13,8 | 5,75 | 17,30 | 6,90 | 21,93 |

| 49 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 14,4 | 3,53 | 10,93 | 4,94 | 14,21 |

| 50 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 14,6 | 3,30 | 8,90 | 4,67 | 12,41 |

| 51 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 14,1 | 3,96 | 10,55 | 4,56 | 13,58 |

| 52 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 14,2 | 3,84 | 15,30 | 5,62 | 18,82 |

| 53 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 14,8 | 2,97 | 8,58 | 3,66 | 12,09 |

| 54 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 14,7 | 3,12 | 13,90 | 3,96 | 15,24 |

| 55 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 15,1 | 2,63 | 7,48 | 4,11 | 11,65 |

| 56 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 14,3 | 3,08 | 6,64 | 4,07 | 9,97 |

| 57 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 15,2 | 3,02 | 8,16 | 3,94 | 12,18 |

| 58 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 14,5 | 2,51 | 6,87 | 4,01 | 11,71 |

| 59 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 14,2 | 2,83 | 8,69 | 3,74 | 12,56 |

| 60 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 14,4 | 2,54 | 7,06 | 3,44 | 11,02 |

Compressive and flexural strength tests were carried out using an MTS Criterion Model C43.504 universal testing machine with a maximum load capacity of 50 kN, fully complying with the EN 196-1 standard. Thermal performance measurements were conducted using type-K thermocouples connected to a digital data logger to continuously monitor internal and ambient temperature variations.

The replacement ratios of 5–20% for ESP and other Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) were selected based on effective ranges widely reported in previous studies on partial cement replacement in mortars and concretes. Previous research indicates that ESP levels between 5% and 20% yield optimal improvements in strength and workability while maintaining mix stability [1, 19, 22, 27, 31, 45, 48]. Similarly, the commonly adopted replacement ranges for SCMs are 10–20% for fly ash [49], 5–10% for silica fume, and 10–30% for blast furnace slag [37]. These proportions were selected in order to maintain consistency with prior studies, make direct comparisons among materials, and identify the most effective substitution levels for sustainable mortar development.

3.1. Flow Table Test

The study evaluated the workability of the mortar mixtures using the flow table test, conducted in accordance with the EN 1015-3 standard. This test determines the flow properties of fresh mortar by measuring its spreadability. The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. (1). The surface of the flow table and the mold were cleaned and moistened before starting the test to prevent sticking.

Flow table test setup. Note: The photograph is intended to illustrate the test apparatus only and does not represent the actual flow result.

The mold was placed in the center of the flow table and filled in two layers. The first layer filled half of the mold and was compacted using 25 strokes of a tamping rod. The second layer was then added and compacted with 25 strokes of the tamping rod to ensure even uniform distribution. The surface was leveled with a trowel, making it smooth and even, and the mold was carefully lifted.

The handle of the apparatus was rotated 15 times, allowing the mortar to spread across the table. The spread diameter was measured along two perpendicular axes, and the average value was recorded as the final flow result.

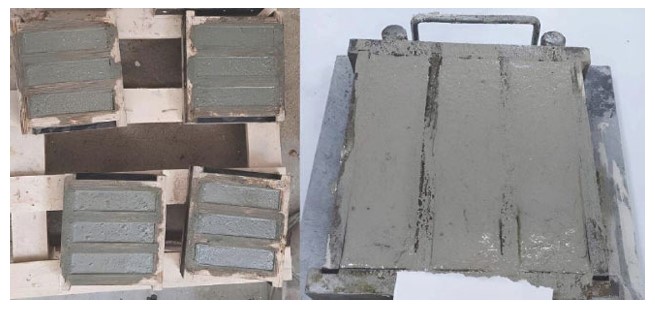

3.2. Compressive Strength and Flexural Strength

The compressive and flexural strengths of the mortars were determined in accordance with EN 196-1, which specifies the standard procedures for evaluating the mechanical properties of cement mortars.

Figure 2 shows the apparatus for compressive strength testing. Freshly cast specimens measuring 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm (Fig. 3) were kept in molds for 24 hours in a humid environment at 20 ± 2°C, as specified in EN 196-1. After demolding, the specimens were cured in water until testing.

Compressive strength testing apparatus.

Freshly cast mortar specimens in molds.

Flexural strength was determined using the three-point bending test, in which a cylindrical load was applied at the midpoint of each specimen until failure. The flexural strength (σ) was calculated using Eq. (1):

Where:

σ = Flexural Strength (Mpa) F = Force At Fracture (N)

L = Span Length (Mm)

B = Specimen Width (Mm) D = Specimen Depth (Mm)

The resulting halves from the flexural test were then used to determine compressive strength, calculated using Eq. (2):

Where:

F=The compressive strength (MPa)

P=Maximum load (or load until failure) to the material (N)

A=A cross section of the area of the material resisting the load (mm2)

A total of 60 mix designs incorporating varying proportions of ESP, FA, SF, and BFS were prepared, resulting in a total of 360 specimens (Fig. 4). Tests were conducted at 7 and 28 days, and the results were statistically analyzed based on the mean and standard deviation for each mixture.

Specimens prepared for compressive and flexural strength testing.

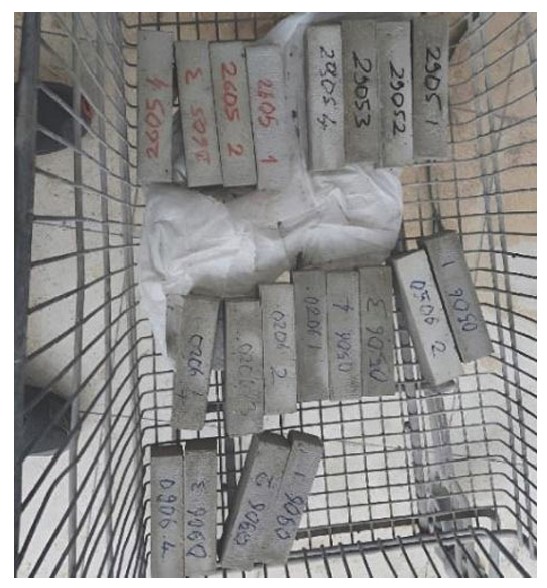

3.3. Shear Strength

Shear strength tests were performed to evaluate the influence of Eggshell Powder (ESP) on the shear resistance of cement mortars. Seven different mortar mix designs, containing varying ESP replacement levels by weight: 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30%, were prepared (Fig. 5). These designs investigated the effect of increasing ESP content on the mechanical behavior of the mortars.

Specimens prepared for shear strength testing.

To test the shear performance of the mortar and concrete specimens, the Z-push-off method was employed. This method applies a controlled load until the concrete fails, enabling an accurate and precise measurement of the shear resistance. We prepared and cured the specimens in accordance with the standards, ensuring all samples were uniform. The tests were performed 28 days after casting to assess the shear behavior at later ages.

The research calculated the shear strength (τ) using Eq. (3):

In this equation, τ represents the shear strength in MPa, while V denotes the maximum load recorded at failure (in Newtons). The term A refers to the cross-sectional area, measured in mm2, that resists the shear force.

Figure 6 shows the test apparatus and setup. The test results provide insight into how using Eggshell Powder (ESP) to replace cement partially affects shear performance.

Shear strength testing apparatus and setup.

3.4. Thermal Performance Analysis

In this study, the thermal performance of cement mortars was evaluated by mixing varying levels of Eggshell Powder (ESP) using four mix designs containing 0%, 15%, 30%, and 50% ESP by weight of cement. The mixes were then cast into prismatic molds measuring 7 cm × 15 cm × 15 cm with 4 cm thick walls, forming sealed rectangular chambers for thermal assessment (Fig. 7).

Thermal performance monitoring setup.

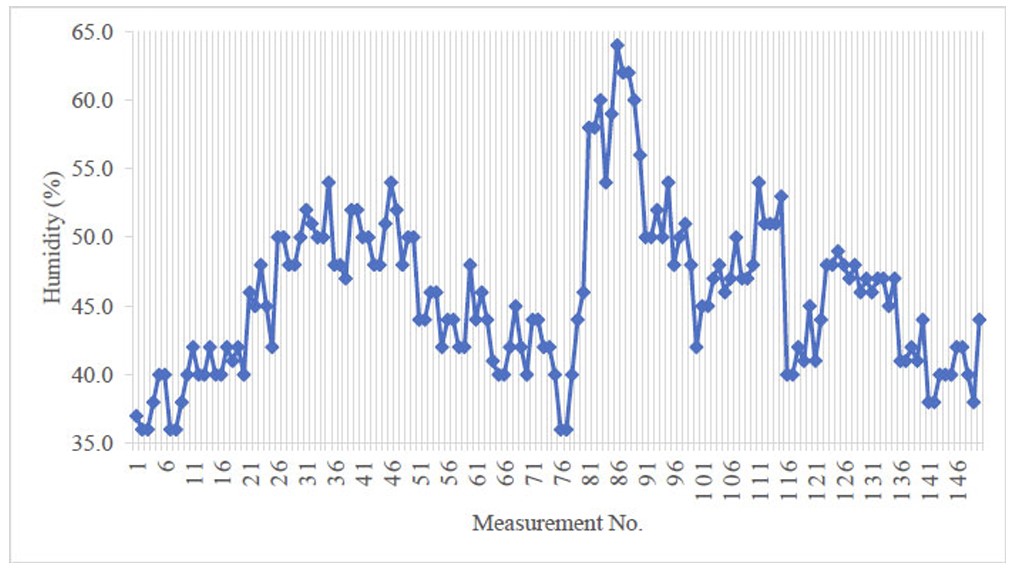

All of the thermal tests were performed in an unheated, uncooled indoor laboratory over a 30-day period. The ambient temperature and humidity were monitored during the test period, and the chambers received the same amount of solar exposure.

To measure the temperature, Type-K thermocouples (±0.5°C accuracy) were embedded in the center of each mortar chamber. Each day, the internal temperature, the ambient air temperature, and relative humidity were measured five times a day (09:00, 12:00, 15:00, 19:00, and 00:00).

In order to be able to interpret the thermal regulation capability of each mix consistently, we then classified each day as hot (> 28°C), mild (18–28°C), or cold (< 18°C) based on the ambient temperature at 12:00. This classification aligns with thermal comfort criteria and facilitates contextual comparison.

The researchers evaluated the performance of each mortar type based on the temperature difference between ambient and internal measurements. This allowed quantification of both the thermal insulation and the passive heat-retention capacities of the different mixtures under variable climatic conditions. Section 4.2.4 presents the experimental results and a detailed thermal performance analysis.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

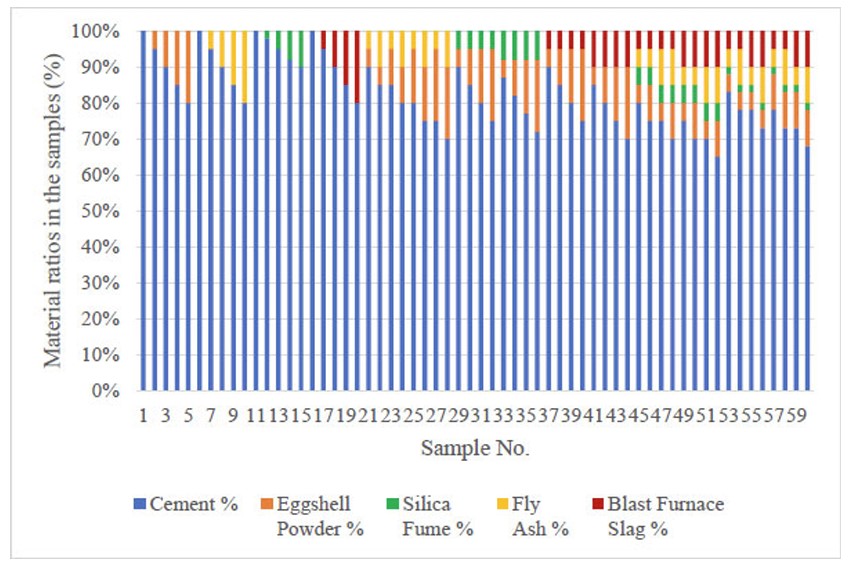

In this section, we present the results of the experimental program, including flow table, compressive strength, flexural strength, and shear strength analyses. These findings were interpreted in relation to material composition, workability, and mechanical performance. Particular emphasis was placed on how variations in Eggshell Powder (ESP) content and the inclusion of Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs), namely Fly Ash (FA), Silica Fume (SF), and Blast Furnace Slag (BFS), influence these properties. Throughout the section, we compared our results with relevant literature to contextualize and validate the findings. Figure 8 illustrates the material composition ratios used in the mortar samples.

Material ratios in the samples.

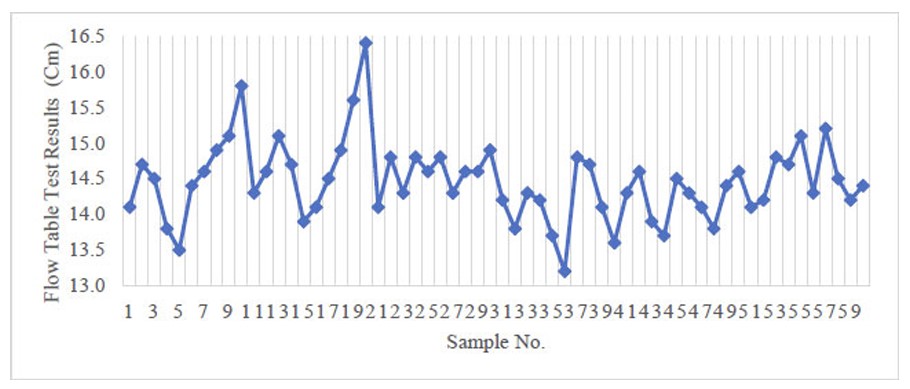

Flow table test results for all mixes.

The specific material ratios, flow table outcomes, and strength metrics (compressive and flexural at 7 and 28 days) for every sample are listed in (Table 4).

In order to evaluate the effects of Eggshell Powder (ESP), both individually and in combination with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), namely Fly Ash (FA), Silica Fume (SF), and Blast Furnace Slag (BFS), the mix design procedure was developed systematically.

The first mortars containing 0-20% ESP (by weight of cement) were produced in 5% increments in order to find the optimum ESP replacement level based on mechanical and thermal performance.

Additional series were then prepared by incorporating FA, SF, and BFS individually at replacement levels that adhered to literature-recommended ranges.

After determining the most effective substitution level for each SCM, we designed combined mixtures by pairing ESP with one SCM at a time (e.g., ESP + FA, ESP + SF, ESP + BFS), followed by a final series containing all four SCMs together.

In total, we prepared 60 distinct mortar mixtures to enable a comprehensive comparison of individual and combined effects on workability, compressive strength, and flexural strength. We aimed to systematically minimize cement consumption and assess synergistic interactions between ESP and industrial by-products with this experimental approach.

Our results showed that this methodology successfully pinpointed the best mix combinations. This allowed us to enhance both mechanical and thermal performance while using significantly less cement.

4.1. Evaluation of Workability via Flow Table Test

To evaluate the workability of the mortar compositions, we prepared 60 mortar samples, each measuring 4 × 4 × 16 cm, and subjected them to flow table tests. Table 4 summarizes the results, and (Fig. 9) presents a visual representation.

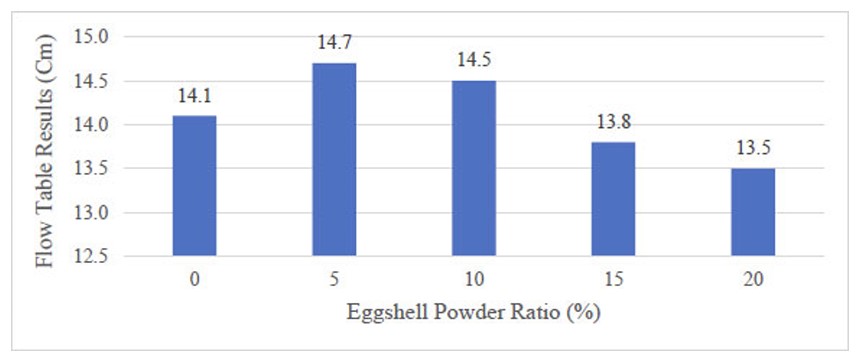

The results of the flow table illustrate the fluidity of the fresh mortars. Fluidity is a key parameter for assessing the ease of placement. Samples containing 5% and 10% ESP (samples 2 and 3) showed slight improvements in flowability when compared to the control (sample 1). As the ESP content increased to 15% and 20% (Samples 4 and 5), flowability was noticeably reduced (Fig. 10).

Flow values with higher ESP content are reduced because of the increased water absorption capacity of fine ESP particles. These particles absorb more water, reducing the amount of water available to lubricate the mix [50]. This observation aligns with previous studies highlighting the adverse impact of high-absorption materials on mortar workability. This suggests that other factors, such as particle size distribution, surface morphology, and the presence of other materials, may also play a significant role [51].

4.2. Compressive Strength and Flexural Strength

The primary objective of this study is to reduce the cement content in mortar mixtures while at the same time maintaining or enhancing compressive strength (CS) and flexural strength (FS). We prepared 360 mortar specimens measuring 4 cm × 4 cm × 16 cm using 60 different mix designs containing varying proportions of Eggshell Powder (ESP), Fly Ash (FA), Silica Fume (SF), and Blast Furnace Slag (BFS). Due to the significant environmental impact of cement production, we examined ESP as a sustainable alternative to cement.

Previous studies reported a reduction in strength when ESP content exceeds 10% by weight. In order to overcome this limitation, pozzolanic materials, such as FA, SF, and BFS, were mixed along with ESP to enhance strength and minimize cement usage.

Change in flow table results with varying ESP ratios.

Initially, mortar mixes were prepared with 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% ESP by weight. Subsequently, FA and BFS were added at 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% by weight, while SF was added at 0%, 2%, 5%, 8%, and 10% by weight. From these mixes, we selected the two proportions yielding the highest strength values for each material: 5% and 10% ESP, 5% and 10% FA, 2% and 5% SF, and 5% and 10% BFS. We then combined these optimal ratios in various ESP-based mixtures to evaluate their collective effects on compressive and flexural strength.

4.2.1. Compressive Strength

The findings of the compressive strength tests demonstrated how ESP content and its combination with Fly Ash (FA), Silica Fume (SF), and Blast Furnace Slag (BFS) affect the hydration kinetics, microstructural development, and overall mechanical performance of the mortar. This provides useful insight into how Eggshell Powder (ESP) interacts synergistically with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs).

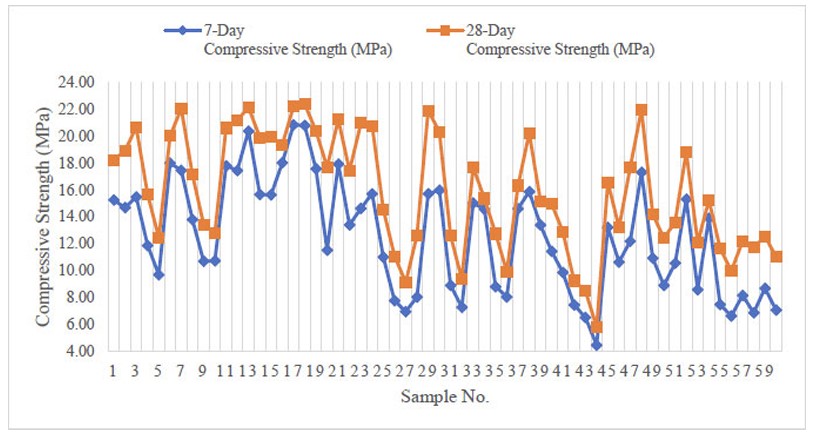

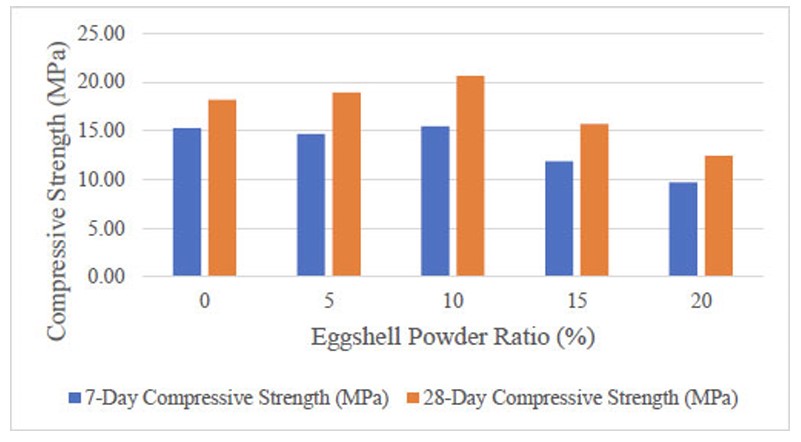

We tested the compressive strength of all 60 mix designs at both 7 and 28 days. A summary of the results is presented in Table 4, and a visual illustration is shown in Fig. (11).

In our first set of mixes (#1–5), we replaced cement entirely with Eggshell Powder (ESP) at varying rates (5–20%). As shown in Fig. (12), modest replacements of 5% and 10% boosted compressive strength by roughly 11% and 14%, respectively, at 28 days compared to the control. These gains were attributed to the fine ESP particles acting as fillers, which help densify the cement matrix. However, raising the replacement levels to 15% and 20% resulted in significant reductions in strength (14% and 32%, respectively). This decline occurs mainly because there is less cement to react, and ESP offers limited pozzolanic activity at such high dosages.

The average 28-day compressive strength of the control mix was 19.54 MPa. Among the 60 mixes, 17 exceeded this baseline value, 9 of which contained ESP. Mix #48 was the strongest, reaching 21.93 MPa, representing a 12% increase over the average and a 20% improvement compared with the weakest control sample. Notably, this mix contained 70% cement, 10% ESP, 10% FA, 5% SF, and 5% BFS. This demonstrates that a 30% reduction in cement content can be achieved without compromising, and even enhancing, mechanical performance.

The incorporation of additional pozzolanic materials, such as FA, SF, and BFS, alongside ESP, contributed significantly to strength development. The pozzolanic activity of FA and SF, particularly their capacity to generate secondary C–S–H gel and fill capillary pores, led to improved matrix densification. BFS, known for its latent hydraulic properties, further supported strength gain over time. For instance, mixes #48 and #52, which contained all three SCMs, exhibited superior performance despite their relatively high ESP levels.

From a microstructural perspective, the combined presence of FA, SF, and BFS with ESP promotes both pozzolanic and filler synergy [8, 11]. The amorphous SiO2 and Al2O3 in FA and SF react with Ca(OH)2 released during cement hydration to form secondary C–S–H and C–A–H gels. This refines the pore network and strengthens the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) [25]. At the same time, BFS contributes additional CaO and latent hydraulic phases, further enhancing long-term strength and microstructural densification [19]. The fine CaCO3 particles in ESP complement these mechanisms by filling micro-voids, acting as nucleation sites for hydration products, and stabilizing early-age C–S–H formation [12, 48]. As a result, the blended systems exhibit a denser, more continuous matrix with fewer interconnected pores. This is consistent with SEM observations from previous studies that reported improved packing density and reduced microcracking at 5–10 wt.% ESP replacement levels [8, 11].

Compressive strength results at 7 and 28 days for all mixes.

Change in 7-day and 28-day compressive strength results with ESP content.

Previous studies are consistent with these findings. They demonstrated that the incorporation of pozzolanic materials along with ESP can markedly enhance compressive strength through complementary microstructural mechanisms [8, 11]. For instance, Teara et al. incorporated up to 30% FA by weight of cement with 0–15% ESP and observed a 16.8% increase in compressive strength for mixes with 5% ESP compared with the control [53]. This enhancement was attributed to secondary C–S–H gel formation and microvoid filling provided by the amorphous silica in FA, which promoted matrix densification and reduced pore connectivity. When higher levels (10-15%) were used, the dilution of reactive clinker phases outweighed the benefits, resulting in lower strength [53].

The existing research reinforces the mechanisms observed in the present experimental program. We found similar trends in our study, where compressive strength decreased by 15–49% in mixes with high ESP and pozzolan content, with the notable exception of mixes #48 and #52. These specific mixes achieved significantly higher strengths due to the balanced synergy among ESP, FA, SF, and BFS. The micro-filler and nucleation effects of ESP, combined with the pozzolanic reactions of the SCMs, produced a denser and more cohesive microstructure that helped mitigate dilution effects [11, 12]. Consequently, low-to-moderate ESP levels (≈ 5–10 wt.%) led to optimized hydration, reduced porosity, and stronger ITZs, which explains the enhanced mechanical performance [48].

While excessive ESP alone may reduce strength due to cement dilution, the addition of supplementary cementitious materials effectively counteracts this limitation, yielding mortars with superior mechanical properties [19]. The combined use of ESP with FA, SF, and BFS presents a promising pathway toward sustainable and high-performance cementitious systems [8, 11]. In the final analysis, the results confirmed that ESP primarily acts as a micro-filler and hydration accelerator at low dosages. Its combination with SCMs transforms it into a synergistic component, enhancing both early- age and long-term performance [8, 12].

4.2.2. Flexural Strength

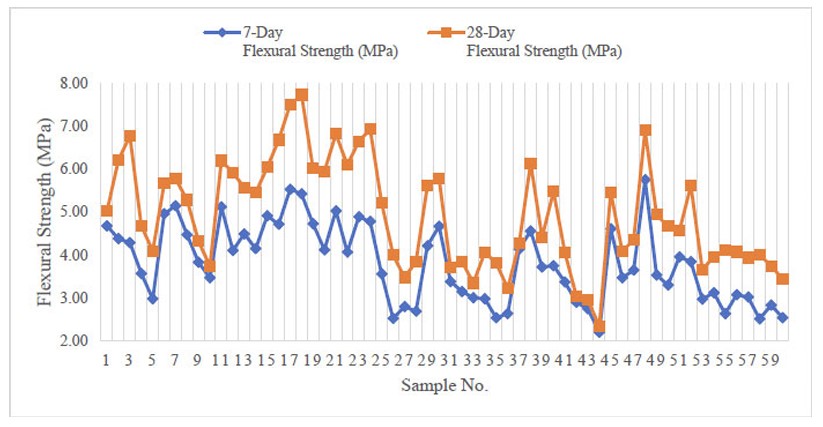

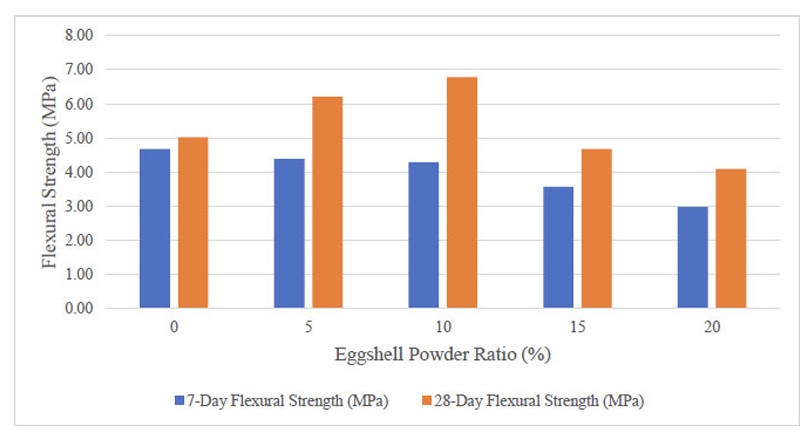

Flexural strength tests were conducted at 7 and 28 days for all 60 mortar mixes to evaluate the tensile performance of the composites. The results are summarized in Table 4 and illustrated in Fig. (13).

In samples #1–5, cement was partially replaced with Eggshell Powder (ESP), as shown in Fig. (14). Mortars containing 5% and 10% ESP (samples #2 and #3) exhibited flexural strength increases of 23% and 35%, respectively, at 28 days compared with the control sample (#1). However, mixes with 15% and 20% ESP (samples #4 and #5) showed corresponding reductions of 7% and 19%, respectively.

The average 28-day flexural strength of the control mortars was 5.89 MPa. When all 60 mixes were evaluated, 14 surpassed this benchmark, including 8 that contained ESP. Sample #24 achieved the highest flexural strength at 6.93 MPa. This corresponded to a 17.6% improvement over the control mortars and a 38% increase compared with the weakest control sample (#1). This mix consisted of 80% cement, 10% ESP, and 10% FA, achieving a 20% reduction in cement content while yielding a notable enhancement in flexural strength. Sample #48 had the second-highest value (6.90 MPa), attaining a 17.1% improvement over the control. This mix contained 70% cement, 10% ESP, 5% SF, 10% FA, and 5% BFS, and demonstrated that a 30% reduction in cement content can be achieved without compromising strength.

Furthermore, 22 of the 60 samples exhibited higher 28-day flexural strength than the control. Of these, 12 contained ESP. This indicates that low-to-moderate ESP content has a positive effect on tensile performance. The most significant strength gains were observed in blended systems that combined ESP with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). These results confirmed a synergistic effect between ESP and SCMs in enhancing tensile capacity, especially when FA and SF were incorporated with moderate ESP levels.

We attribute this synergy to the microstructural refinement and pozzolanic reactivity of the blended systems, which significantly improve load distribution and crack resistance. FA contributes to tensile strength primarily due to enhanced interfacial bonding and a refined pore structure, while SF improves matrix density and crack propagation resistance. This is consistent with trends in compressive strength, demonstrating the effectiveness of blended pozzolanic systems in producing high- performance mortars.

Flexural strength results at 7 and 28 days.

Change in 7-day and 28-day flexural strength results with ESP content.

It is worth noting that mixes containing high ESP content alone exhibited poor performance. However, we largely mitigated this limitation by combining ESP with appropriately proportioned SCMs [53, 54]. These experimental observations are consistent with previous studies that have investigated how ESP affects flexural performance across diverse cementitious systems.

From a microstructural perspective, the improvement in flexural strength observed in mixes containing 5–10% ESP is largely due to the formation of a denser, more cohesive matrix. The fine CaCO3 particles within the ESP act as nucleation sites for early hydration. This accelerates the formation of C–S–H gel and promotes a more uniform distribution of hydration products. Such refinement strengthens the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the paste and aggregates, which helps delay microcrack initiation and reduces crack propagation under flexural loading. Similar mechanisms were reported by Gowsika et al. [31] and Parthasarathi et al. [40], who observed that incorporating 5–10 wt. % ESP enhanced flexural strength through improved C–S–H gel development and pore refinement within the ITZ.

When ESP is combined with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), such as FA and SF, the amorphous SiO2 and Al2O3 components react with Ca(OH)2 released during hydration to form secondary C–S–H and C–A–H gels. These products fill capillary voids, refine the pore structure, and enhance the compactness of the matrix. This synergistic reaction is consistent with findings reported by Hama [39] and Pliya and Cree [45], who reported that low-to-moderate ESP replacement levels improve tensile and flexural strength through enhanced particle packing and the formation of additional hydration products, whereas higher ESP levels lead to dilution effects and reduced cohesion.

The micro-filler and nucleation effects of ESP, coupled with the pozzolanic reactivity of SCMs, generate a more homogeneous and well-bonded microstructure. These combined effects explain the superior flexural strength observed in ESP–SCM blended mortars in this study, aligning with SEM- based evidence from prior research [8, 11, 12, 23, 40, 48].

In contrast, Binici et al. [44] and Bhuvaneswari [55] reported reductions in flexural strength at high ESP replacement levels, which they attributed to weaker aggregate bonding and limited CaO activity. Conversely, Ing and Choo [43] demonstrated that ESP with higher calcium content (~95%) can offset this limitation, yielding up to 22.9% higher flexural strength due to accelerated hydration and enhanced microstructural bonding. These comparative findings highlight that ESP performance is strongly influenced by its chemical composition, fineness, and replacement ratio.

Overall, both the literature and the present experimental results indicate that ESP acts as a micro-filler and nucleation enhancer at low dosages, promoting a denser ITZ and improved crack resistance, while its synergy with SCMs enables further microstructural refinement. This consistent evidence across multiple studies confirms that the observed mechanical enhancements are primarily driven by hydration acceleration, secondary C–S–H formation, and uniform stress transfer through a densified matrix.

4.2.3. Shear Strength

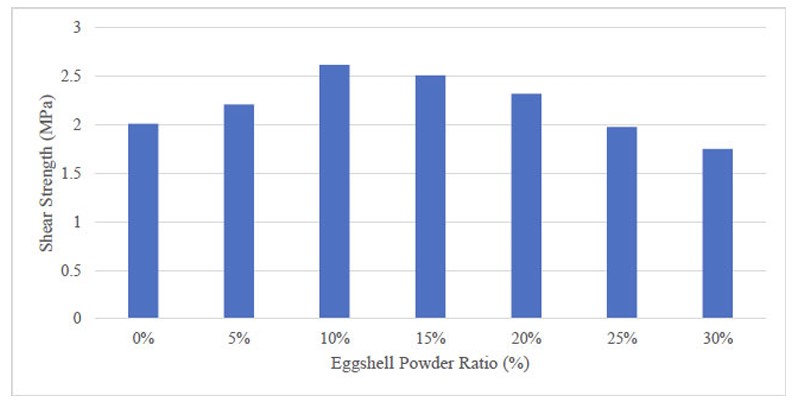

For the shear strength tests, seven cement mortar samples were prepared: one control mix without Eggshell Powder (ESP) and six containing ESP at 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% by weight of cement. The shear strength tests were conducted on the 28th day using the Z-push-off method, and the results are presented in Fig. (15).

Shear strength test results of all mixes.

The shear strength of the control sample without ESP was 2.01 MPa. The sample containing 5% ESP exhibited a strength of 2.21 MPa, while the 10% ESP specimen achieved the highest value at 2.58 MPa. Specimens with 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% ESP recorded strengths of 2.51 MPa, 2.32 MPa, 1.98 MPa, and 1.75 MPa, respectively. Notably, the 10% ESP mix demonstrated a 28% increase in shear strength compared with the control [56]. Similarly, the 15% and 20% ESP mixes showed 24% and 15% higher shear strength values, respectively.

The decline in shear strength observed in the 25% and 30% ESP mixtures can be attributed to the excessive dilution of cement within the mortar matrix, which reduces binder efficiency. These results indicate that partial cement replacement with ESP enhances shear performance up to a 20% substitution level, whereas higher replacement ratios lead to diminished strength. This reduction likely stems from the insufficient availability of reactive cementitious components necessary for proper hydration and bonding.

Microstructurally, the improved interfacial adhesion and matrix cohesion are responsible for the enhancement in shear strength at 10 to 20 wt.% ESP. The fine CaCO3 particles in ESP act as nucleation centers during early hydration, promoting the generation of additional C–S–H gel and strengthening the bond between the cement paste and sand grains. This mechanism results in a denser interfacial transition zone (ITZ), enhancing shear load transfer capacity. Similar microstructural phenomena were reported by Hamada et al. [11], Sathiparan [19], and Nandhini and Karthikeyan [8], who associated ESP’s filler effect and calcium-rich composition with improved bonding in cementitious systems.

At higher ESP levels (> 20 wt.%), excessive CaCO3 content can increase porosity and hinder the formation of a continuous C–S–H gel network, thereby reducing cohesion. Amin et al. [7] and Tchuente et al. [57] similarly reported that excess calcium-based fillers disrupt gel continuity and weaken the microstructural framework, findings consistent with the reductions observed in this study at 25–30 wt.% ESP.

The results of this study confirmed that ESP improves shear strength up to a 20% replacement ratio, whereas higher dosages lead to dilution-induced strength loss. These outcomes, consistent with previous studies, indicate that low-to-moderate ESP levels (≈10–15 wt.%) are optimal for enhancing shear performance [48, 56-58].

4.2.4. Thermal Analysis

We conducted the thermal performance analysis using cement-based mortar samples containing Eggshell Powder (ESP) at replacement levels of 0%, 15%, 30%, and 50% by weight. These samples were used to construct closed chambers measuring 7 cm × 15 cm × 15 cm with a wall thickness of 4 cm. We recorded the long-term thermal measurements at five specific times of the day (09:00, 12:00, 15:00, 19:00, and 00:00) using type-K thermocouples. During each test, ambient temperature, relative humidity, and internal chamber temperatures were monitored continuously.

To evaluate thermal performance systematically, we divided the experimental period into three ambient temperature categories: hot days, mild days, and cold days, based on temperature readings recorded at the specified intervals over a 30-day period.

The categorization criteria were as follows:

- Hot Days (Above 28°C): Days in which the ambient temperature was above 28°C, typically between 12:00 and 15:00. On these days, the thermal stress conditions are high and are suitable for evaluating the samples’ cooling capacity and their ability to maintain a comfortable temperature in spite of the heat.

- Mild Days (18–28°C): Days in which the ambient temperature was between 18°C and 28°C. This range falls within thermally comfortable conditions, and the demand for heating or cooling is minimal. These days are ideal for assessing the passive thermal regulation properties of mortars.

- Cold Days (Below 18°C): Days in which the temperature was below 18°C, with conditions suitable for evaluating the ability of the samples to retain heat and maintain comfortable temperatures inside when the ambient temperatures were low.

The temperature thresholds for these categories were based on distribution trends observed during the testing period. They are consistent with established thermal comfort models in the literature. This classification enables a structured and comparative analysis of ESP-containing mortars under varying climatic conditions.

Segmenting the data into these categories enabled the study to provide a comprehensive understanding of how ESP-modified mortars respond to different temperature regimes. It demonstrated their potential for enhancing indoor thermal comfort across diverse environmental settings.

We recorded the lowest ambient temperature as 4.2°C at 09:00, when solar radiation was minimal (Fig. 16). For the samples containing 0%, 15%, 30%, and 50% ESP, we measured corresponding internal temperatures of 2.9°C, 4.1°C, 3.9°C, and 4.0°C, respectively. It was observed that the control mix without ESP had an internal temperature 1.3°C lower than the ambient temperature, whereas the ESP-containing samples maintained temperatures closer to the ambient temperature, indicating improved thermal stability.

On a mild day with an ambient temperature of 20.1°C, varying internal thermal behaviors were observed across the samples. It was found that the control and 15% ESP samples recorded temperatures of 18.0°C and 19.6°C, respectively, remaining below the ambient value. In contrast, our measurements showed that the 30% and 50% ESP samples exhibited slightly higher internal temperatures of 20.9°C and 21.1°C. Notably, the 50% ESP mix showed an internal temperature 1°C higher than the ambient temperature, demonstrating its superior thermal retention.

On the warmest morning, as the ambient temperature reached 30.4°C, our measurements highlighted the effective cooling capacity of the ESP-modified samples. While the control sample recorded 26.9°C, we found that ESP inclusion significantly reduced internal temperatures. Specifically, the 15% ESP mix achieved the lowest reading at 24.2°C, followed closely by the 30% and 50% mixes at 24.9°C and 25.2°C, respectively. We observed that this cooling effect reached up to 6.2°C above ambient, demonstrating that ESP contributes substantially to improved thermal comfort under high-heat conditions.

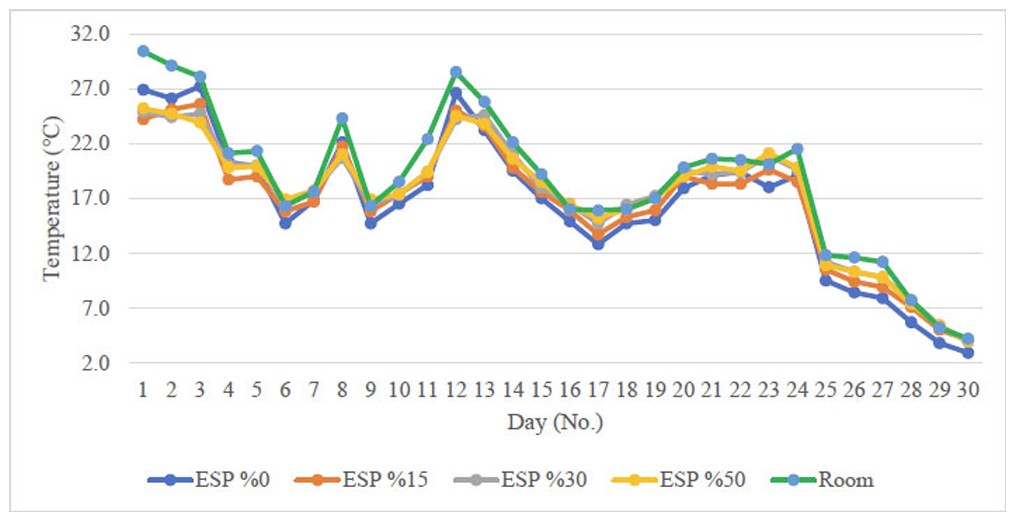

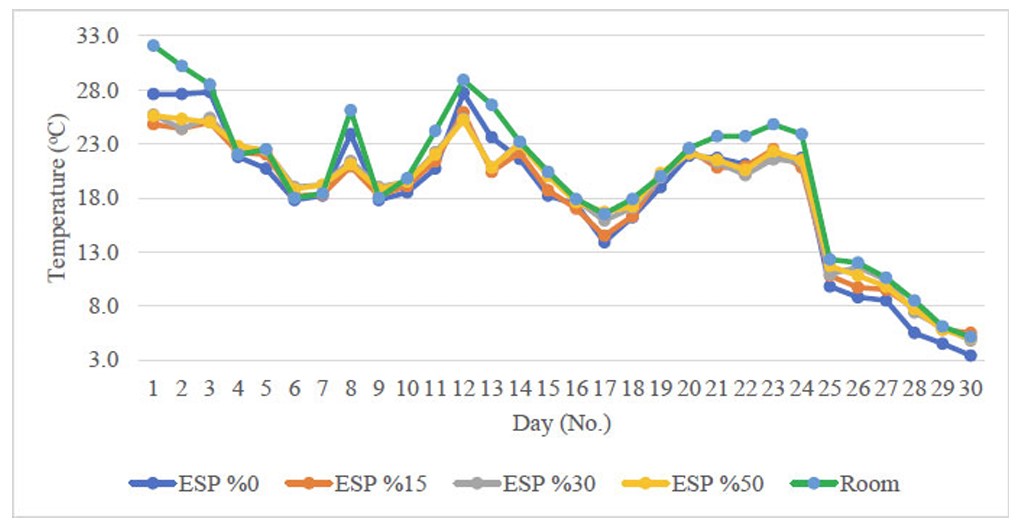

By 12:00, we observed that solar radiation significantly influenced the environment, causing a noticeable rise in temperatures (Fig. 17). During this peak period, we recorded the lowest ambient temperature as 5.1°C. Our measurements showed that internal readings varied across the mix designs: the control sample remained coldest at 3.4°C, while the ESP-modified samples showed better heat retention. Notably, it was found that the 15% ESP sample demonstrated a slight advantage, maintaining an internal temperature of 5.5°C, which was 0.4°C higher than the ambient environment. During our tests under mild weather conditions (20°C ambient), we observed distinct thermal behaviors among the samples. While we recorded a cooler internal temperature of 19.0°C for the control sample, our data indicated that the inclusion of ESP generally improved heat retention. It was identified that the 50% ESP mix, in particular, exhibited the superior performance; we measured it at 20.3°C, maintaining a temperature 0.3°C higher than the surrounding environment.

On a warm day with an ambient temperature of 32.1°C, the thermal benefits of ESP were observed. While we measured an internal temperature of 27.6°C for the control sample, the ESP-modified samples remained significantly cooler, with readings ranging from 24.8°C to 25.7°C. Most notably, our data showed that the 15% ESP mix achieved an internal temperature 7.3°C lower than the outside environment, highlighting the material's exceptional capacity for passive cooling under heat stress.

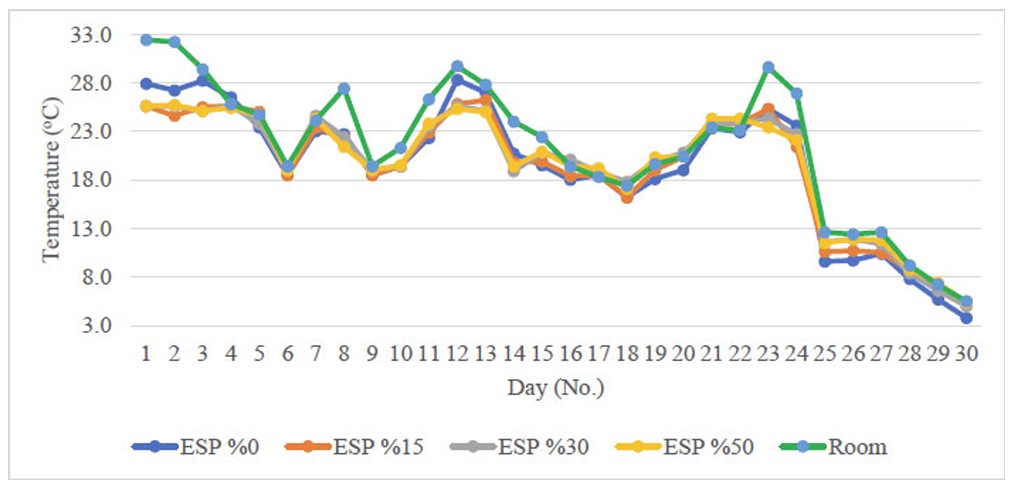

At 15:00, when the ambient temperature reached its daily peak due to solar intensity (Fig. 18), we recorded a baseline ambient temperature of 5.5°C. Varying thermal responses were observed across the mix designs. It was found that the control sample remained significantly cooler at 3.8°C. In contrast, our measurements for the 30% and 50% ESP samples were 5.0°C and 5.4°C, respectively. Notably, we observed that the 15% ESP sample reached 5.5°C, perfectly matching the ambient temperature, whereas the other samples indicated limited heat retention under these conditions.

On a mild day with an ambient temperature of 20.4°C, we measured internal temperatures of 19.0°C, 20.4°C, 20.8°C, and 20.4°C for the 0%, 15%, 30%, and 50% ESP samples, respectively. The 30% ESP sample reached the highest internal temperature, exceeding ambient by 0.4°C, while the remaining samples had internal temperatures equal to or slightly below ambient.

On the warmest day, when the ambient temperature peaked at 32.4°C, we observed a distinct cooling effect in the ESP-modified samples compared to the control. We measured an internal temperature of 27.9°C for the control mix, which was 4.5°C lower than the ambient air. In contrast, our data revealed that all ESP-containing samples (15%, 30%, and 50%) maintained a consistent and significantly lower temperature of 25.6°C. This represents a reduction of up to 6.8°C relative to the surrounding environment, underscoring the superior passive cooling potential of ESP-modified mortars under high solar exposure.

Internal temperatures at 09:00 over 30 days for samples with different ESP levels.

Internal temperatures at 12:00 over 30 days for samples with different ESP levels.

Internal temperatures at 15:00 over 30 days for samples with different ESP levels.

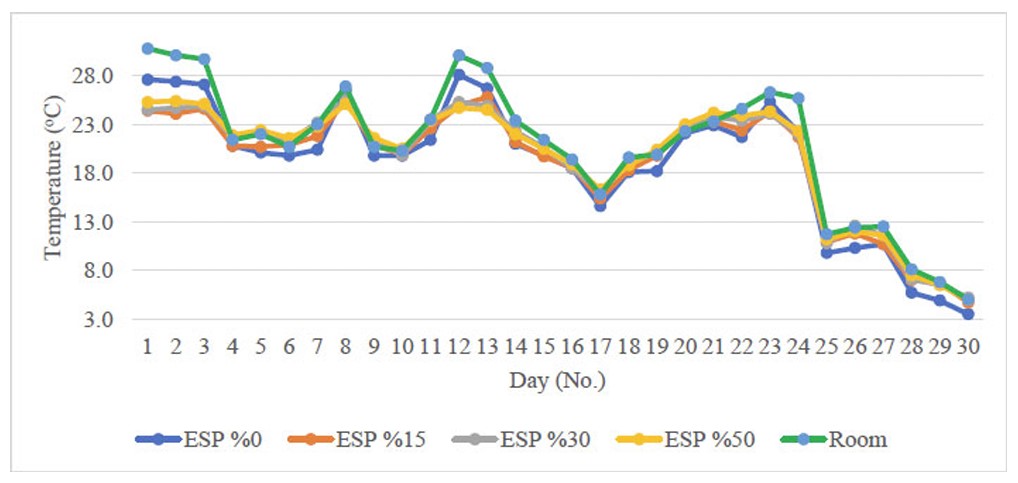

Internal temperatures at 19:00 over 30 days for samples with different ESP levels.

By 19:00, as the sun's influence diminished and ambient temperatures began to decline (Fig. 19), we recorded the lowest ambient temperature at 5.0°C. Our measurements for the internal temperatures of the 0%, 15%, 30%, and 50% ESP samples were 3.5°C, 4.7°C, 5.2°C, and 5.0°C, respectively. We observed that the 30% ESP sample maintained an internal temperature 0.2°C higher than the ambient value, whereas the 50% ESP sample equalized with the ambient environment.

On a mild day with an ambient temperature of 19.9°C, we measured internal temperatures of 18.2°C, 19.8°C, 20.2°C, and 20.4°C for the 0%, 15%, 30%, and 50% ESP samples, respectively. Our data showed that the samples containing 30% and 50% ESP exceeded the ambient temperature by 0.3°C and 0.5°C, demonstrating enhanced heat-retention capability during evening conditions.

On a warm evening, as the ambient temperature reached 30.8°C, we observed notable differences in thermal comfort performance. We recorded an internal temperature of 27.6°C for the control mix.

However, our measurements for the ESP-containing mortars were significantly lower; we found values of 24.4°C, 24.5°C, and 25.3°C for the 15%, 30%, and 50% ESP mixes, respectively. This data indicates that ESP modification can maintain internal temperatures up to 6.4°C below ambient, offering improved thermal comfort as external temperatures decrease.

At midnight, the ambient temperature reached its lowest daily level (Fig. 20). On the coldest night, with an ambient temperature of 4.1°C, we measured internal temperatures of 2.7°C, 4.2°C, 4.0°C, and 4.0°C for the 0%, 15%, 30%, and 50% ESP samples, respectively. It was found that the 15% ESP sample exhibited an internal temperature 0.1°C higher than the ambient value, demonstrating a slight heat-retention advantage under low-temperature conditions.

On a mild night, when the ambient temperature was 20.4°C, we recorded internal temperatures of 19.2°C, 20.1°C, 20.9°C, and 20.7°C for the 0%, 15%, 30%, and 50% ESP samples, respectively. Our data indicated that the samples containing 30% and 50% ESP maintained internal temperatures 0.5°C and 0.3°C higher than the ambient value, confirming their enhanced thermal stability in moderate nighttime conditions.

On the warmest night, with an ambient temperature of 28.8°C, we identified distinct thermal advantages in the ESP-modified samples. While we measured an internal temperature of 27.9°C for the control group, our readings for the ESP samples were noticeably lower, ranging from 25.4°C (30% ESP) to 25.9°C (15% ESP). It was observed that these modified mortars sustained internal temperatures up to 3.4°C lower than the ambient environment, indicating a significant passive cooling effect and improved nighttime thermal comfort.

We recorded the humidity measurements at five distinct time intervals over a 30-day period, as shown in Fig. (21). This figure illustrates the temporal variation in ambient humidity, providing a clear visualization of daily trends and facilitating a comprehensive interpretation of moisture fluctuations within the testing environment.

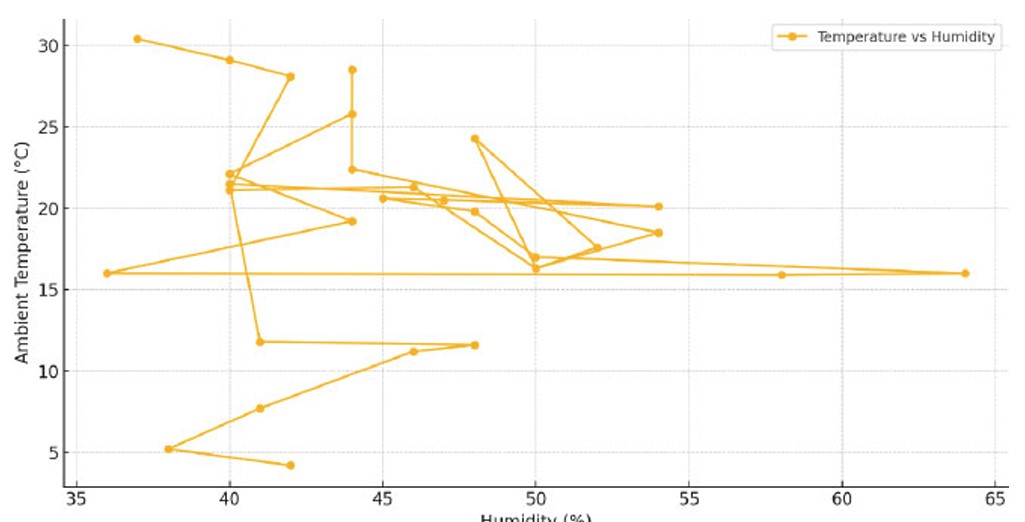

In this study, we measured ambient humidity and temperature in closed chambers constructed using cement-based mortar samples containing different proportions of Eggshell Powder (ESP), along with a control sample without ESP. Our analysis indicated that ambient humidity had no significant influence on the observed temperature variations, confirming that material composition, rather than atmospheric moisture, primarily governed the thermal performance of the specimens. The relationship between ambient temperature and humidity is presented in Fig. (22).

Internal temperatures at 00:00 over 30 days for samples with different ESP levels.

Humidity measurements recorded at different time intervals over 30 days.

Relationship between ambient temperature and humidity.

Correlation analysis revealed a weak negative relationship between ambient humidity and temperature (r = -0.10). This low correlation coefficient suggests that fluctuations in ambient humidity exert a negligible influence on temperature variation. These results show that cement-based mortars inherently exhibit passive resistance to humidity-driven thermal changes. However, to gain a more comprehensive understanding, we recommend further investigations under diverse environmental conditions and extended exposure durations.

Our results clearly demonstrated that Eggshell Powder (ESP) markedly enhanced the thermal performance of cement-based composites [8, 11, 16, 59]. It was observed that mortars with higher ESP contents, particularly 30% and 50%, exhibited superior thermal regulation, maintaining internal temperatures closer to or below ambient levels under both hot and cold conditions. These outcomes highlighted the potential of ESP as a sustainable additive for improving the thermal efficiency of construction materials.

This improved thermal performance can be attributed to the porous morphology and high calcium carbonate (CaCO3) content of ESP, which collectively reduce the effective thermal conductivity of the mortar matrix. The fine ESP particles introduce irregularities in heat-transfer pathways and increase phonon scattering, thereby restricting heat flow through the composite. In addition, closed micropores in ESP-modified mortars trap air pockets that act as natural thermal insulators. These combined effects result in lower heat conduction during hot periods and enhanced heat retention during cooler conditions.

Previous studies [11] [8] similarly confirmed that calcium-rich fillers, such as ESP, can decrease thermal conductivity and increase thermal inertia in cementitious systems, leading to slower heat transfer and greater heat-retention capacity. This dual effect, slower heat ingress and delayed heat release, accounts for the reduced diurnal temperature fluctuations observed in the ESP-modified chambers.

Furthermore, the influence of ambient humidity on internal temperature was found to be statistically insignificant, indicating that the thermal improvements in ESP-containing mortars are predominantly governed by their intrinsic microstructural and thermal properties, rather than by external environmental factors.

Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that the current experimental setup employed small-scale laboratory chambers. While these results provide clear evidence of the passive thermal regulation potential of ESP-modified mortars, large-scale field investigations are necessary to confirm their practical applicability under real climatic conditions. Future studies should focus on long-term outdoor testing, building-scale prototypes, and dynamic thermal modeling to assess the scalability and durability of ESP-integrated systems.

In summary, ESP-based mortars enhance thermal regulation while remaining largely unaffected by humidity variations, offering a reliable solution for energy-efficient construction across diverse climatic zones. The findings confirm that ESP’s micro-filler action and pore-inducing behavior are key to its passive heat-moderation mechanism, validating its role as a sustainable and eco-efficient additive for next-generation cementitious materials.

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Scope

The observed reduction of up to 7°C in internal temperature demonstrates a clear potential for improved thermal insulation capacity in practical construction applications. When scaled to building envelopes, such reductions could lead to a measurable decrease in cooling energy demand in hot climates and lower heat loss in cold environments, underscoring the broader applicability of ESP- modified mortars for enhancing passive thermal regulation.

However, the findings of this study are based on short-term laboratory tests (7–28 days) and small- scale specimens. Long-term durability assessments, such as freeze–thaw resistance, chloride ion penetration, sulfate attack, and carbonation, were not included in the current work. Therefore, the results should be interpreted within the context of early-age mechanical and thermal performance. Future research should extend the experimental framework to include large-scale wall prototypes, dynamic thermal simulation models, and comprehensive durability and microstructural analyses (e.g., SEM, XRD, TGA) to validate the scalability and long-term stability of ESP-modified mortars under realistic environmental conditions.

CONCLUSION

Within the scope of short-term laboratory testing, the findings indicate that low-to-moderate ESP incorporation (≈5–10 wt.%), in combination with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), provides a balanced enhancement in both mechanical and thermal performance. The optimal blended mix (70% cement, 10% ESP, 10% FA, 5% SF, and 5% BFS) achieved approximately 12% higher compressive strength and 17.1% higher flexural strength at 28 days compared with the control, while the 10 wt.% ESP variant reached nearly 28% higher shear strength at the same age. Small passive chambers (7 × 15 × 15 cm; 4 cm wall thickness) exhibited peak indoor temperature reductions of up to ≈7°C during hot periods, indicating a meaningful passive thermal response under the tested conditions. However, workability losses became evident above 15 wt.% ESP, and higher-ESP mixes failed to retain the mechanical gains observed at ≤10 wt.%. These results collectively suggest that low- to-moderate ESP dosages, particularly when combined with FA, SF, and BFS, offer a promising cement-reduction strategy consistent with the filler–packing and nucleation mechanisms reported in previous studies.

The interpretation and generalization of these results, however, are subject to several limitations. The thermal evaluation was performed using small-scale indoor chambers without active HVAC systems and did not include direct measurements of thermal conductivity (λ) or specific heat capacity (Cp); therefore, building-scale energy implications cannot be directly inferred. In addition, the number of replicates for certain datasets (e.g., shear strength) was limited, so although the observed trends are consistent, further statistical validation (e.g., ANOVA, confidence intervals) is required. The study duration was limited to 7–28 days, and critical microstructural and durability indicators, including SEM/XRD/TGA, freeze–thaw resistance, chloride ingress, sulfate attack, and carbonation behavior, remain to be explored.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: E.T.: Contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, experimental work, data curation, formal analysis, and writing the original draft preparation; R.A.: Took part in supervision, project administration, experimental guidance, writing, reviewing, editing, and validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ESP | = Eggshell Powder |

| SCMs | = Supplementary Cementitious Materials FA – Fly Ash |

| SF | = Silica Fume |

| BFS | = Blast Furnace Slag CS – Compressive Strength FS – Flexural Strength |

| SS | = Shear Strength |

| w/b | = Water-to-Binder Ratio |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animal testing.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies involving human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

FUNDING

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to the Construction Materials Laboratory at Istanbul Technical University for providing access to essential equipment and materials used in this study. Their support greatly contributed to the successful completion of the experimental work.